India’s villages are home to the majority of the country’s population and, by extension, its future human capital. For decades, the national education conversation has rightly focused on expanding school infrastructure, enrollment, and attendance. That expansion has delivered reach.

Yet, when rural learning is viewed beyond enrolment figures, a quieter limitation becomes visible.

While schooling has expanded, access to learning beyond the classroom has not expanded at the same pace.

In most villages, learning remains tightly bound to school hours, prescribed textbooks, and teacher-led instruction. Outside that window, time is consumed by farming, household responsibilities, wage work, and caregiving. Time exists. Learning access often does not. Reading, revision, and exploration fade, not because interest disappears, but because resources do.

Any serious conversation about revitalising rural India, therefore, has to move beyond schooling alone and confront a more fundamental question: how learning time itself is enabled or constrained in village life.

That Question First Becomes Visible Only When Access Briefly Appears

This shift is rarely visible in theory. It becomes visible when access enters the school’s ecosystem, even briefly.

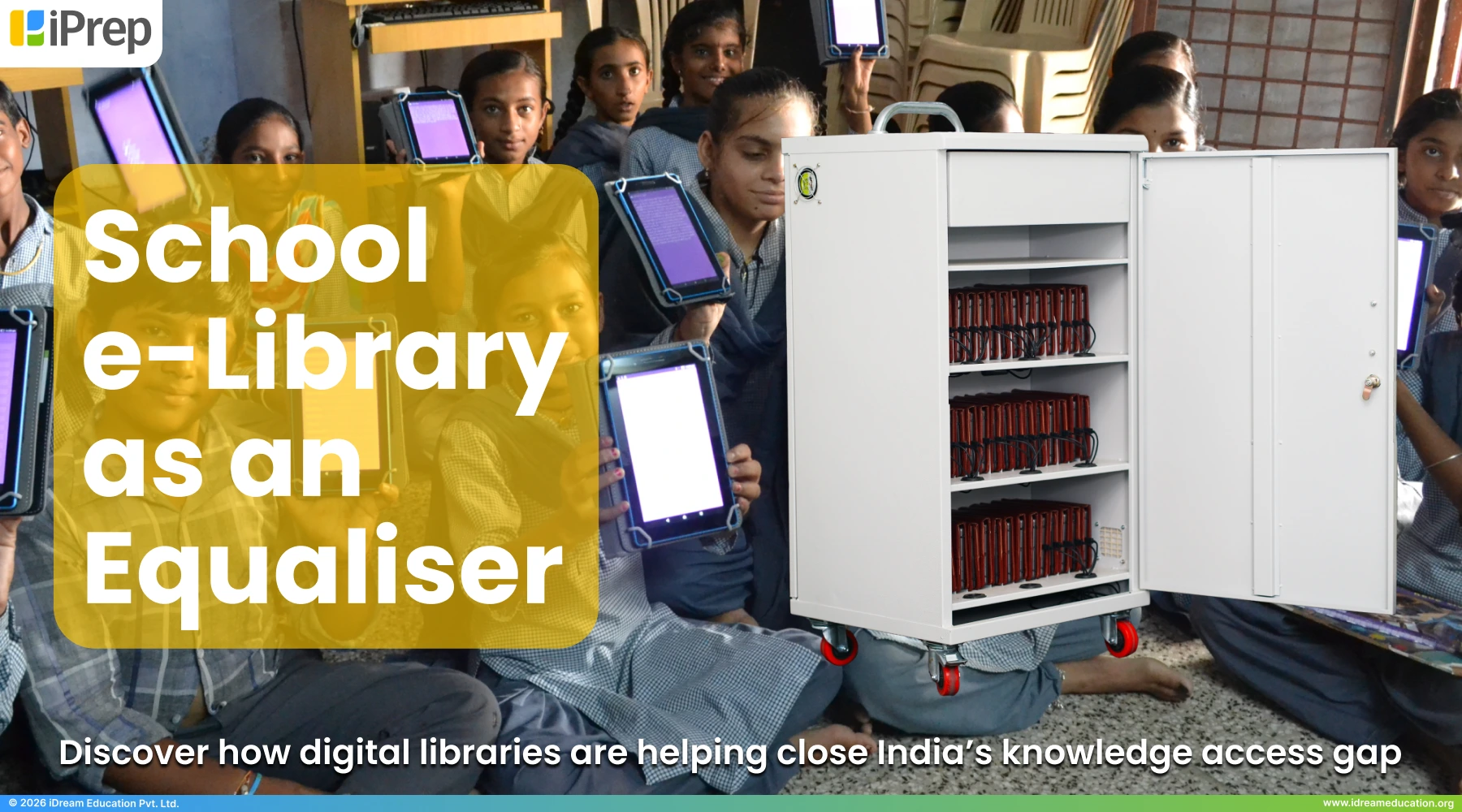

In a government school in rural Rajasthan, a digital library was introduced as part of regular school activity. Tablets preloaded with offline digital reading resources were made available to students during school hours.

Within two to three months, usage data revealed a clear pattern. One student, Nidhi, was accessing far more reading content than her peers. When this pattern was examined, the explanation was uncomplicated. She shared that she had always enjoyed reading, but there was no library in her village, no books available at home, and no functional school library she could regularly use.

The digital library did not introduce a new behaviour.

It surfaced one that had been constrained.

This moment matters not because it is unique, but because it exposes a structural truth that often remains hidden: learning interest can exist independently of learning access, and behaviour responds quickly when access appears.

Still, decisions about learning interventions in rural education cannot be drawn from a single classroom-level observation.

At this point, attention moves from observed student attendance to whether sustained access leads to measurable learning outcomes.

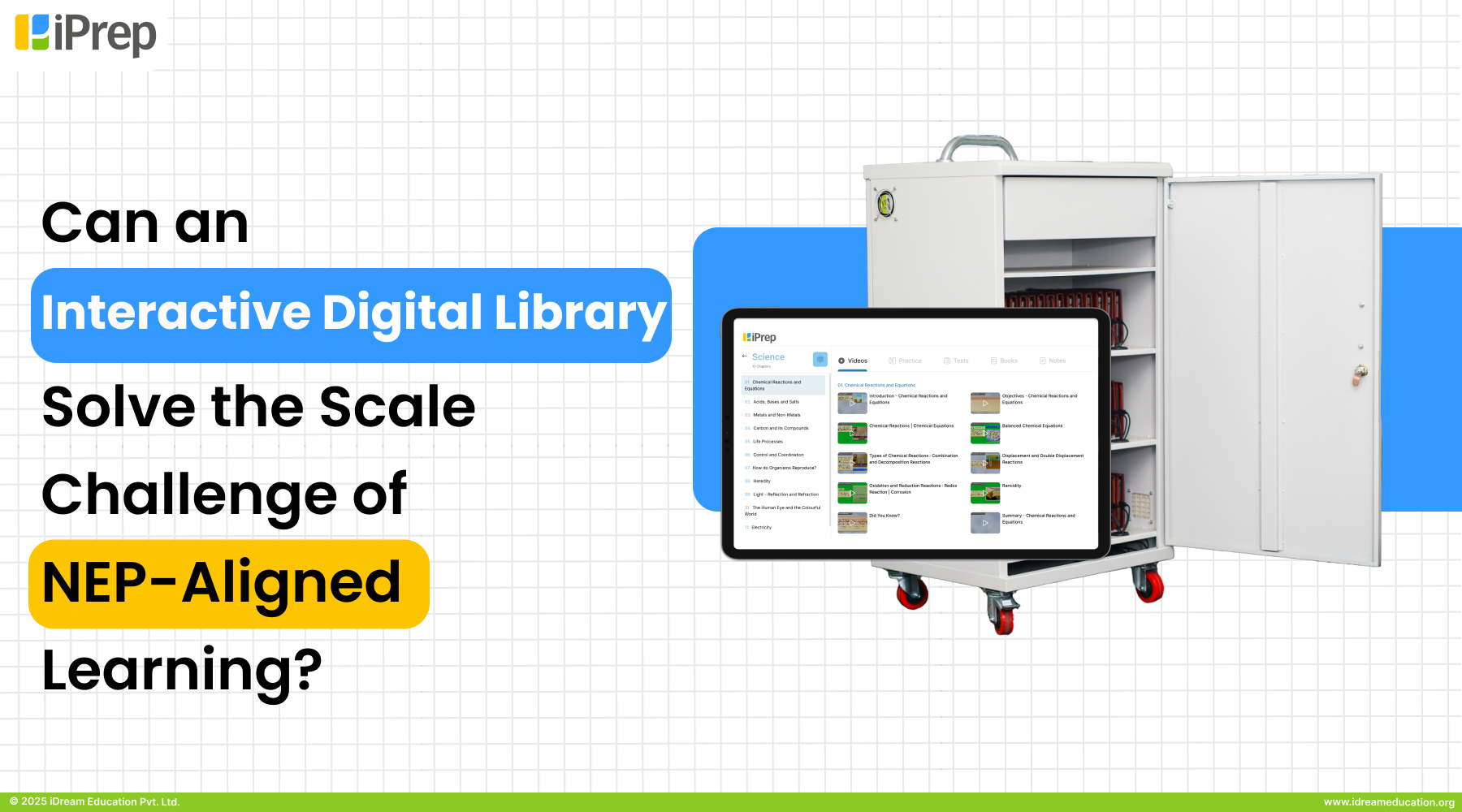

Once the learning behaviour of students is observed, the question inevitably deepens. Does sustained access to digital learning resources translate into measurable academic outcomes, or does engagement remain superficial?

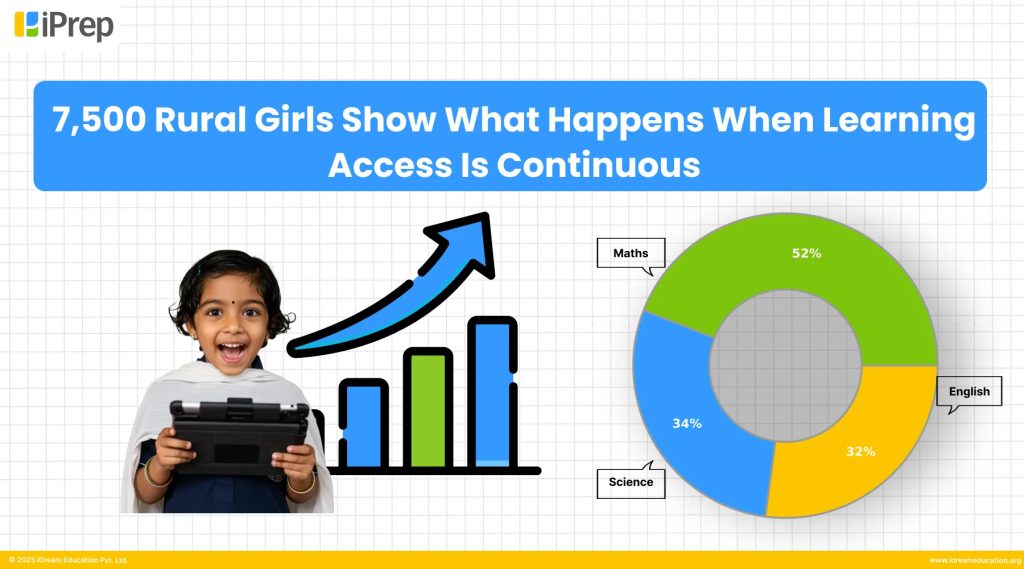

That evidence emerged through a separate implementation in Uttar Pradesh, where a non-profit organisation facilitated access to a digital library for students at scale. In this programme, 7,500 girl students were provided devices loaded with digital learning content for home-based use. Onboarding and ongoing support ensured that access was sustained rather than episodic.

After one year of consistent usage, an independent third-party evaluation assessed subject-wise learning outcomes. The findings were unambiguous:

- English: 32% improvement

- Science: 34% improvement

- Mathematics: 52% improvement

These outcomes are significant not only for their magnitude, but for the conditions under which they were achieved. The improvements emerged through offline digital resources, used in real rural environments, without reliance on continuous internet connectivity.

At this point, the conversation no longer centres on whether access matters. It turns to what kind of access made these outcomes possible.

When similar outcomes begin to appear across different geographies, attention naturally moves away from results and towards structure.

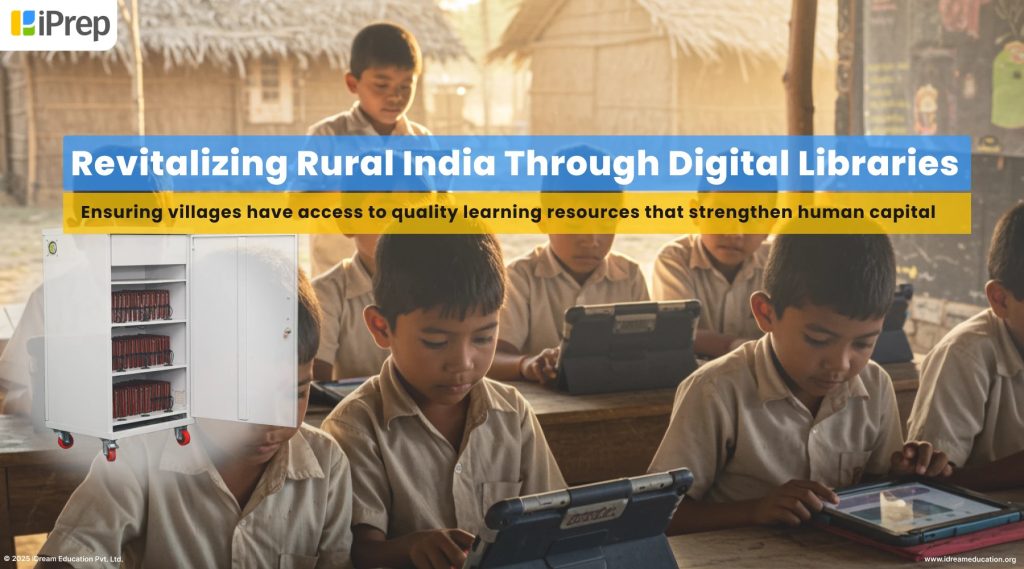

Across both the Rajasthan school and the Uttar Pradesh programme, the digital library for rural India followed a consistent physical and operational form, shaped by classroom realities rather than technological ambition.

The setup was simple and deliberate:

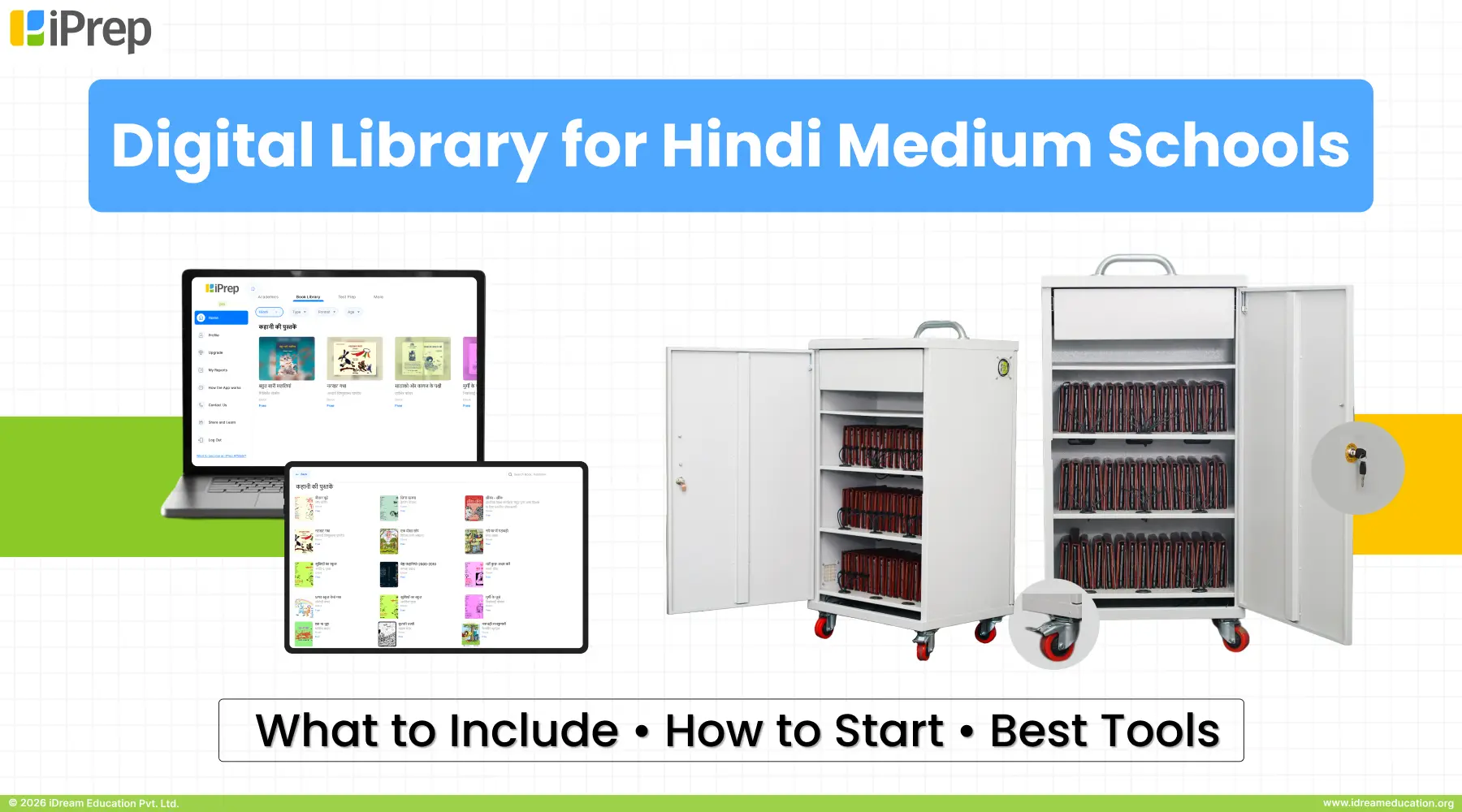

- Tablet charging station for schools with central racks supporting shared tablets across multiple classrooms

- Each device carries an SD card loaded with thousands of digital reading/learning resources for schools.

- Content mapped across subjects and grades, available in English, Hindi, and relevant local languages

- Fully offline operation, without reliance on internet access

- Low power requirements and lightweight devices, allowing flexible use across classrooms and shared spaces

What emerges from this pattern is not a feature list, but a conclusion: a e-library for rural schools works only when it understands existing constraints rather than assuming new infrastructure.

Understanding the structure, however, still leaves one question unanswered: can such an Indian school system survive daily rural school conditions?

What Ultimately Determines Whether a School-Level Model Aligns With Indian School Realities?

Rural India operates under conditions that are well understood, yet often underestimated: intermittent electricity, limited connectivity, and constrained technical support.

The digital library model aligns with these realities through a small number of deliberate choices:

- Preloaded digital learning and reading resources stored on durable SD cards for instant access

- Curriculum-aligned content in local languages matching state textbooks across grades 1-8

- Fully offline access without internet dependency, eliminating WiFi and data plan costs

- Low-power, shared devices, enabling schools to function without specialised maintenance teams. It allows digital content for government schools to reach many learners without one-to-one device ownership

These choices make the digital library device durable rather than delicate. Digital library resources become continuously accessible rather than episodic, embedded rather than dependent on constant intervention.

Revitalising Rural Learning Ultimately Depends on How Access Is Treated

Revitalising rural India is not only about livelihoods or employment. It is also about how time is used, how digital education continues beyond formal hours, and how access to knowledge becomes predictable rather than incidental.

Digital libraries do not replace schools, teachers, or curricula. They strengthen them by ensuring that digital content for government schools remains available, relevant, and usable across years.

The discussion around digital libraries, therefore, is no longer about whether they are effective, but about how learning access is structured, sustained, and embedded within existing rural education systems. And how well can rural bodies, including gram panchayats and zila parishad, adopt them? From a policy perspective, the Government supports the creation of Digital Libraries under its various key schemes, including Samagra Shiksha, PM SHRI schools, with budgets allocated. The question is how well state governments and rural governments adopt these for large-scale impact. In this context, choosing a digital library provider that can work with state and rural bodies becomes as important as the hardware or content itself.

If you are engaged in education programmes or CSR initiatives focused on long-term learning outcomes, you can explore how digital libraries support real-world rural learning is a conversation worth having.

Reach out to us at 917678265039 or write to us at share@idreameducation.org.